Václav Fiala’s sculpture, ‘Tower for Jan Palach’, being exhibited in Sculpture by the Sea, Bondi this year, is a soaring tribute to the act of self-immolation by Jan Palach on 19 January 1969 in Prague’s Wenceslas Square to protest the Soviet Union-led Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia the previous August that crushed the liberalising reforms of the Prague Spring.

Palach’s death is one of the most tragic episodes in the dark years of the twentieth century for Czechoslovakia that ended in late 1989 with the most wonderful of revolutions, the Velvet Revolution as it is known among Czechs and the Gentle Revolution by the Slovaks.

As strange as it may initially seem, the idea and realisation of Sculpture by the Sea is inexorably linked to the tragedy and the inspiring redemption of Czechoslovakia, and the two countries which peacefully separated to become the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic in 1993. The links between a happy go lucky art exhibition on the Sydney coast of the lucky country and the gentle velvet revolution that freed the tortured soul of Czechoslovakia are on two different but intertwined levels: a love of and nurturing of sculpture; and the question of how to live one’s life and contribute to society.

In a series of mass public demonstrations which showed the ultimate power of the powerless, the Czech and Slovak peoples overthrew the totalitarian Communist rulers who had been propped up by the Soviet Union, bringing to an end the tragic century for this magnificent central European nation.

Born in far happier times at the end of World War One as one of the most cultured, civilised, educated and prosperous countries in the world(1), Czechoslovakia was torn apart just 20 years later by Nazi Germany in 1938-39, before sinking into the mire of post World War Two communism behind the omnipresent Iron Curtain for over 40 years.

To understand the Velvet Revolution it must be remembered that in the mid 1960’s the initially gradual reforms of the Czechoslovak Communist leader Alexander Dubček, which sought to release the shackles of the Stalinist years by creating ‘socialism with a human face’, rapidly accelerated with freedom of expression and freedom of the press.

What followed was an astounding cultural re-awakening with film makers including Miloš Forman and Jan Němec, writers such as Milan Kundera, Ivan Klíma, and playwrights such as Václav Havel quickly gaining global reputations. Newspapers, magazines, theatre, poetry, rock music flourished where they had recently been suppressed and what would have landed people in jail, sometimes just months before, now made them national heroes. Then in August 1968, for the second time in 30 years unwelcomed tanks rolled in. This time the Soviet Army, the liberators of 1945, returned to lead the invasion that brought to an abrupt end the Prague Spring. Overnight the heady idealism, freedoms and artistic creativity were shut down. With no end in sight to imprisonment within the Soviet bloc tens of thousands fled Czechoslovakia before the borders were sealed, many of them coming to Australia. Political, social, cultural and economic freedom was extinguished for a further 30 years.

Out of tragedy sometimes comes the most marvellous of redemptions. This was the case for Czechoslovakia in 1989 and we are honoured to join the Czech and Slovak governments in celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution by inviting 10 leading artists to exhibit at Sculpture by the Sea, Bondi. This includes David Černý’s ‘Pink Tank of Prague’, a reprise of his famous guerrilla art action in 1991 when he painted bubble gum pink the memorial to the Russian tank crews of 1945 that had quickly come to be seen as a symbol of oppression after the 1968 invasion.

Michael Žantovský, in his biography of Václav Havel (the playwright, writer, dissident and first President of post Communist Czechoslovakia) offered an illuminating insight into the personal individual element so fundamental to the Velvet Revolution.

“Rarely has a political movement been born neither of an idea of changing the world, nor of the opposition to the other ideas of changing the world, but rather of an individual, internal, psychological need to find a balance in one’s life. The ambition was simultaneously modest and staggering. Reaching it required nothing more and nothing less than staying true to oneself. Its corollary was ignoring or resisting the demands of the outside world to suppress, alter or mask one’s own identity, demands that are present in any type of world, but which were ominously imperative and persistent in the world of post-totalitarian socialism.” (2)

Communist Czechoslovakia, suffocated the individual.

In ‘The Power of the Powerless’, written in 1978, Havel neatly defined the relationship between the Communist State and its citizens and how the powerless can wield their power. As summarised by Žantovský, Havel gave the example of the greengrocer who displays the Communist slogan in his shop window ‘Workers of the World Unite!’ without believing in it, and as strange as it sounds, without the authorities expecting him to believe it either. ‘Individuals … need not accept the lie. It is enough for them to have accepted their life with it and in it. For by this very fact, individuals confirm the system … (and) are the system.’

The power of the powerless is to create and safeguard a space to live in truth and to bring together small but every increasingly larger groups who had not succumbed to the State to create an alternative culture to that sanctioned by and based on the lies of the State. This second or parallel culture was most conspicuously achieved by the samizdat, or underground, publication of novels, plays and essays by writers such as Kundera, Klíma and Havel that were hand written or individually typed and clandestinely passed from hand to hand during the years of repression following the crushing of the Prague Spring.

The cultural, emotional and societal value of the samizdat publications was enormous and led to or co-existed alongside ‘parallel’ music and theatre scenes and backyard art exhibitions. Most importantly for those who participated in this parallel culture, it enabled them to live in truth partly or entirely removed from the life based on lies required by the State.

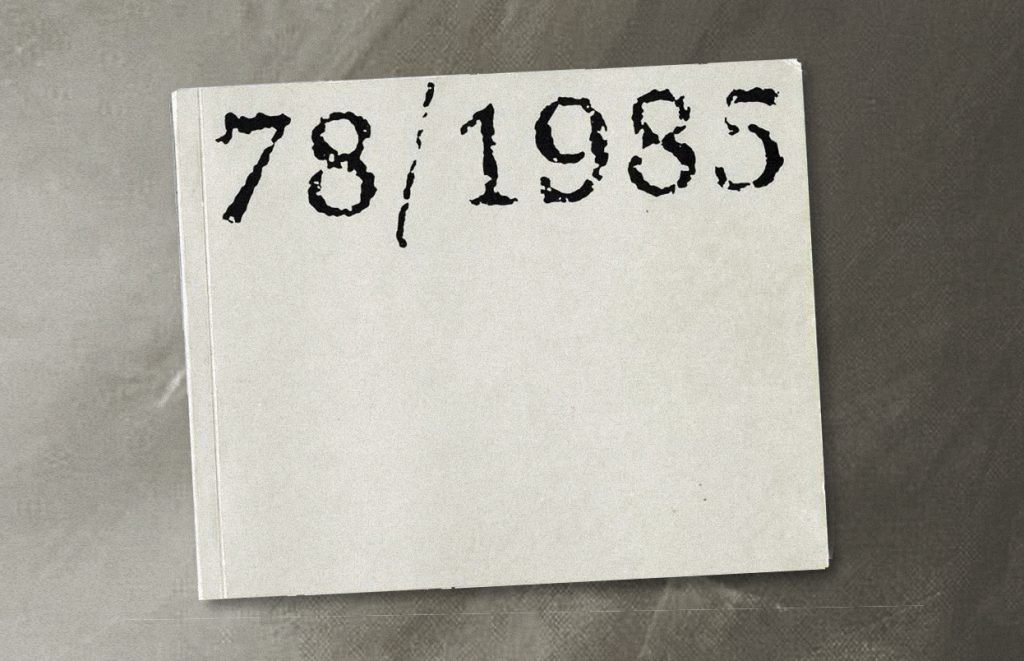

Cover of the illegally published book on 78 artists living in Prague prohibited from exhibiting by the Czechoslovakia Communist regime.

In the Visual Arts one of the most important features of the parallel culture was the samizdat publication of ‘78 / 1985’ in 1987. Featuring 78 of the leading sculptors and painters the book was intended to “make it known that the visual arts too were alive, free and far from servile … to make the public, at home and abroad, aware that other artists than those recognised by the state and the party existed and were working.”(3) The artists selected for the book lived in Prague, with this geographic limitation chosen to help safeguard the secrecy of the project.

“Grey bricks must be picked up” was the code to let the artists know the 1,000 illegally printed books were ready for collection from the secret warehouse. It had not been an easy process to produce the book that became known as the Grey Brick and which was originally scheduled for publication in 1985, the 40th anniversary of the founding of the post World War Two Republic of Czechoslovakia. Delays and hurdles were many, including the arrest of the publisher, the interrogation of members of the editorial board and poor quality paper requiring a re-print, but “the hardest task was to get everything together from each and every individual. The art world is hardly the best disciplined community … we were up against unkept promises, wrong information, incorrect attributions to the photographs, material handed in incomplete and other types of shortfall.” (4) With artists, some things never change!

Žantovský notes, “the strangely bookish tinge to modern Czech history. It often seems that the most important battles … have been fought in theatres, in lecture halls and on bandstands, rather than on battlefields or in parliaments.” Charter 77 encapsulated the intellectualism at the heart of the Czechoslovak opposition to the Communist state in 1977. The Charter 77 document, a statement of human rights by an eclectic group comprised of former Communist party leaders from the reform era of 1968 and the broader opposition with Havel at its core, threw down the moral gauntlet to the Communist state. Charter 77 established a committee for Human Rights to monitor adherence to the international covenants on individual rights that the Czechoslovak Communist state had signed up to. By doing so the signatories to Charter 77 established themselves as the alternative to the Communist party – not the done thing in a one-party state. In retaliation, each of the 242 signatories to Charter 77 lost their jobs, were persecuted and many including Havel were thrown in jail. Yet as Žantovský notes, Charter 77 was “the human rights movement that all the power, might and force of the regime would be unable to suppress.”

For all the moral foundations laid for the Velvet Revolution it was university students in Prague and Bratislava whose protests from the twentieth anniversary of the self-immolation by Jan Palach in January 1989 (known as Palach Week) to the fiftieth anniversary of the violent Nazi clamp down on the student protests of 17 November 1939 that were crucial to the overthrow of the Communist party. When the 17 November 1989 protest in Prague by over 15,000 students was violently broken up by riot police it led to an out pouring of anger among the wider population. In typical Czechoslovak style artists, actors and students went on strike. The Public Against Violence organisation was founded on 19 November in Bratislava and the same day in Prague Civic Forum was founded, in a theatre, by among others Václav Havel, with these groups instrumental in carrying the revolution forward. By now the Berlin Wall had been down for over a week and the general population thronged into the streets. The first mass protest in Prague on 20 November numbered some 100,000 people, followed the next day by the first mass demonstration in Bratislava. On 25 November, almost 800,000 people demonstrated in Prague with their keys jingling in their hands calling on the Communist government to lock the door behind them when they left.

While it is debateable whether the Czechoslovak Communist state would have used military force in an attempt to crush the Velvet Revolution had the Berlin Wall not come down and the liberalising reforms of Mikhail Gorbachev’s Soviet Union not begun to take hold (5), the Czechoslovak people had in Václav Havel and his colleagues the moral basis and moral leadership ready to lead the Velvet Revolution and the transition to a society free of the shackles of the police state. Ultimately this is why the dictators failed and the supposedly powerless prevailed.

Shortly after the Velvet Revolution, in the widespread spirit of celebration of the times, an exhibition of the 78 artists in the Grey Brick was held in 1991. Known as ‘78/1991’ the sculptures were set among the ruins of the 13th century Klenová Castle in western Bohemia near the town of Klatovy where the painters were exhibited in the local gallery. The Grey Brick exhibitions were held every year until 1994 as a manifestation of the Velvet Revolution, celebrating the new found freedom to exhibit, with the exhibitions organised by Václav Fiala.

I was taken to the Grey Brick exhibition ‘34 / 1993’ by friends who were studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague (and who had been denied entry to the Academy during the Communist years) and we were allowed to stay on the floor of the chateau attached to Klenová Castle. That night after a liberal dose of very average Communist era red wine (with plastic bottle tops) we played a mixture of theatre sports meets hide and seek among the ruins of Klenová Castle and the sculptures.

These elaborate parlour games were a key part of the evening entertainment of the artistic set during the Communist years when almost everything worthwhile in terms of culture and entertainment was banned – except the singer Karel Gott (think Cliff Richard with a hint of Richard Burton) and ‘Skippy’ which was shown on TV. This is one of the reasons the Czechs and Slovaks like Australia so much, we have kangaroos but not Karel.

It was during this visit to Klenová in 1993 that I immediately understood the drama and theatricality of sculpture and decided sculpture should be the art form of the free to the public cultural event that I thought I might one day produce. During the previous four years the idea of producing a free cultural event had intermittently kept coming to my mind, with one idea or another, rejected or building on the raison d’être for the event. Up until that moment the concept of the event had no artistic focus, instead the focus had only been on the benefits that might flow to society and how by being free to visit there was no nexus between the number of visitors and the bottom line, so there was no financial temptation to influence the artists in what they wished to create. In this way the ideas behind Sculpture by the Sea had been greatly influenced by the idealism of the Prague Spring, resulting in the conviction that individuals could explore their own creativity to make the world a slightly better place, that free to the public cultural events add greatly to the sense of community and community goodwill, that the world was far too commercial and needed more ‘free things’, and that the dreams of artists and their freedom of expression should be nurtured for their individual and society’s general benefit.

23 years on from the first Sculpture by the Sea, Bondi exhibition we welcome to Australia the latest wave of Czech and Slovak sculptors who would not have been allowed to travel or exhibit here 30 years ago. Let us also remember the tyrannies of the last century and the corrupting influence of dogma. In the words of Ivan Klíma, “The social catastrophes that befell humanity in (the twentieth century) were assisted by an art that worshipped originality, change, irresponsibility, avant-gardism, that ridiculed all former traditions and sneered at the consumer, the audience in the gallery and the theatre, that took smug delight in shocking the reader instead of responding to questions that tormented him … (The totalitarian regimes) assumed the avant-garde’s dismissive attitude to tradition and traditional values, to genuine memory of humanity, and then tried to force upon literature a counterfeit memory and false values.”(6)

David Handley AM

Founding Director

Sculpture by the Sea ‘111 / 2019’

With thanks to Hana Flanderová, the Czech Consul-General to Sydney for introducing me to Michael Žantovský’s ‘Havel a Life’, to Václav Fiala for a copy of Jiří Šetlík’s catalogue essay for the ‘78/1991’ Grey Brick exhibition, and to Jana Dostálová for taking me to Klenová in 1993.

1. As an aside, the steel for the Sydney Harbour Bridge came from Czechoslovakia. 2. ‘Post- totalitarian socialism’ was the term given by Václav Havel to contrast the period of absolute totalitarianism during the Stalinist years with the period know as the ‘Normalisation’ in the 1970’s that followed the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 by the Soviet Union and most of the other Warsaw Pact countries. 3. Jiří Šetlík, ‘The Grey Brick’ catalogue essay, 1991. 4. Jiří Šetlík, ‘The Grey Brick’ catalogue essay 1991. 5. In Mikhail Gorbachev’s autobiography he recounts with dismay his realisation on a visit to Prague in 1969 the universal hatred of the Czechoslovak people for Russia. 6. Ivan Klíma, ‘Literature and Memory’ published in the collection of essays titled ‘The Spirit of Prague’.